What Louisiana, Kentucky, and Texas can teach us about value in higher education.

Earlier this month we hosted the first of a series of conversations to showcase how states and systems across the country are grappling with some serious issues plaguing higher education in the U.S., specifically:

- The demographic cliff that is forcing institutions to rethink recruitment and student engagement;

- Rising student debt and questions about the return on investment that have eroded public confidence; and

- A growing recognition that there is a persistent misalignment between education and workforce needs.

Why Do We Need Higher Ed?

At the same time, there is a growing need for degrees. According to Georgetown University Center for Education and Workforce, 42% of jobs in 2031 will require at least a Bachelor’s Degree. We need to address higher ed’s “value” challenge – and soon.

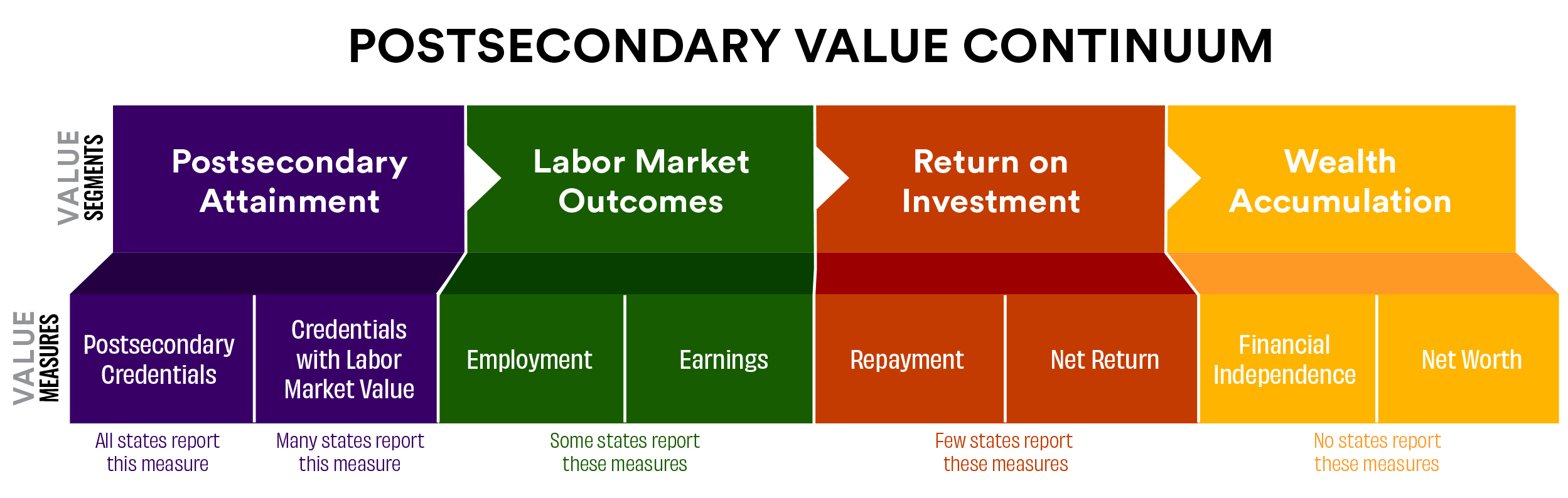

As part of our new postsecondary value framework—The Great Value Shift—ESG developed the Postsecondary Value Continuum to build on the value-focused work of the past decade and help states grapple with different ways to measure value. The Continuum has four main segments: postsecondary attainment, labor market outcomes, return on investment, and wealth accumulation. These segments grow progressively more complex and attempt to capture students’ journeys to long-term economic security and mobility. Within each segment, “value” can be quantified using different high-level measures.

This framework comes directly out of what ESG has learned in our work in the field and supporting our clients. At the beginning of the continuum are measures of postsecondary attainment, which remain an important indicator of how well our higher education sector is serving students. Moving along the continuum, incorporating measures that capture labor market outcomes adds a layer of nuance to our understanding of value. Next, is return on investment which combines what it costs to actually earn a credential and what happens after that credential is earned. Finally, the last part of the continuum—and the most difficult to capture—is wealth accumulation. If we subscribe to the belief that higher education is the great conduit for economic mobility, then we need to consider net worth and financial independence of the students that pass through our institutions.

So what did we hear from some of the leaders engaged in this work?

In Louisiana, state leaders began to look at labor market outcomes data for all credentials of value—including short term workforce credentials and industry based certifications, which they refer to as Validated Skills and Learning—and that created a new opportunity to see, quite clearly, what can happen from an economic mobility perspective when someone obtains these credentials.

“About 70% of the people who are served by [our] program, do not have a sustainable family income to be able to support themselves or their families,” noted Dr. Tristan Denley of the Louisiana Board of Regents. “When they graduate the program, more than 70% of them now do have a family income that is above that ALICE Threshold. We see their family income increase by about $20,000 for many people, that’s doubling their family income just because, literally, because of that new credential that they earn. Now, if that’s not value, I don’t know what it is.”

Kentucky has focused heavily on affordability of higher education, implementing a “last dollar” model to many of their scholarships to lower income families to bridge the financial gap for students who have already exhausted other forms of assistance, such as federal and state aid, gifts, grants, and scholarships.

“In the last five years, we’ve had the lowest tuition raises in the history of Kentucky,” said Dr. Aaron Thompson, president of the Kentucky Council of Postsecondary Education. “But we also concentrated on debt because [so many people] were saying ‘I can’t afford to go to college.’ So, we got our colleges and universities to say we will give last-dollar in on unmet needs. So in the last five years, what has happened? Well, only two out of five students now are graduating with debt, and of that two out of five, we’ve reduced their debt load by 34% so all of these things, we have to talk about that value proposition to the needs of the population that we’re talking about, and that’s what we’ve done, and it’s working.”

In San Antonio, education leaders are building coalitions with others in the community—leveraging the data on postsecondary attainment and economic outcomes to galvanize a localized approach to increasing attainment

“We found that a majority of high school graduating high school seniors did not go on to college within our community—only 46% throughout our county actually went on to enroll in college,” recalled Dr. Mike Flores, Chancellor of Alamo Colleges District. “We have what’s called a moonshot here at Alamo Colleges, and that’s to partner with others to end intergenerational poverty in our community through education and training. [Through this work] we’ve been able to move the needle from 46% to 54% in five years.”

I am grateful for these leaders, who offer valuable insights into how the larger field can rethink value, emphasizing the importance of data, workforce alignment, and student success. The Great Value Shift is not just a report; it’s a call to action. It’s an invitation to join a national conversation and contribute to a more relevant, responsive, and valuable higher education ecosystem.

We are always looking to showcase higher ed leaders who are making significant progress with this work at their respective states and institutions. Do you want to share your story? Let’s connect! Reach me at klovett@edstrategy.org.