Spotlight: The Christensen Institute’s Work on Social Capital

We know that doors to opportunity are not opened solely by students’ academic experiences or success. Social capital—benefits and opportunities derived from networks and connections—matters tremendously for success in postsecondary education and training and beyond. To understand more about the importance of social capital and ways to support students in building and leveraging it, we spoke with Julia Freeland Fisher, Director of Education at the Clayton Christensen Institute, which recently released a new playbook on building and strengthening students’ networks to help them thrive.

Tell us a little bit about the Christensen Institute and the work that you do.

We are a small, nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank that studies innovation of the public sector. We were founded by Harvard Business School professor Clay Christensen, who unfortunately passed away last year, but who’s best known in the business world for coining the term “disruptive innovation.” Our education practice has focused historically on innovations that scale access to student-centered learning, largely powered by technology, and online and blended learning. But my own research really focuses on a different component of the opportunity equation, which is students’ access to networks and who they know. Looking at the research on social mobility and access to opportunity, we know that the opportunity sits at the cross section of what you know and who you know, and we see a real innovation opportunity there.

What is social capital and why does it need to be a consideration for education leaders looking to advance equitable student outcomes?

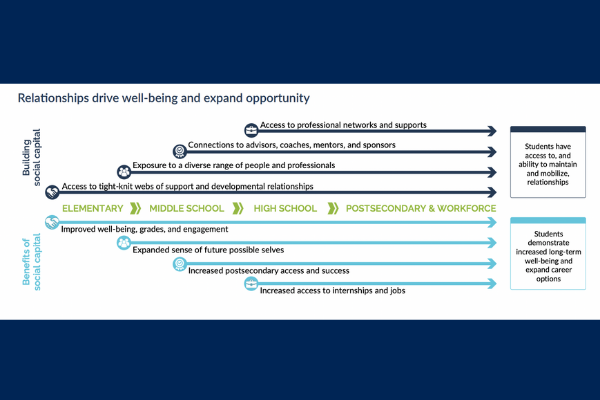

The basic premise, if we’re to really boil it down, is the idea that our networks contain value. So if you compare social capital to financial capital (what we have and can buy with that) and human capital (what we know and can do and the labor market will reward us for), social capital, which is who we know, offers its own value. But conceptually it can feel murkier. Unlike financial capital that you can hold in your hand or human capital that you can see reflected back at you in terms of skills or labor market returns, social capital manifests as everything from emotional support, financial support, information, referrals, sponsorship, and more. Social capital is so important despite the fact that it can feel murky because it matters immensely for access to opportunity. An estimated half of jobs come through personal connections. So insofar as our schools view themselves as enabling pathways to opportunity, as much as they need to focus on skills and what students know, they can’t afford to ignore who students know.

Who has a role to play in helping students build networks and develop social capital? How does this differ between the high school and postsecondary levels?

We anchor a lot of our research in the work of Mario Luis Small, who’s a sociologist at Harvard University. One of his big contributions to the literature on social capital is the idea that institutions are themselves brokers of social capital. So as opposed to what some of the earlier literature may have suggested, which is that you primarily inherit social capital, institutions are places where social capital can be built. We think our institutions, our K-12 school districts, our postsecondary institutions, our workforce development organizations all have a role to play because they are already brokers of social capital. The opportunity they have, though, is to start to get more deliberate, equitable, and data-driven in that practice.

So what could this look like in both high school and postsecondary? One is first understanding who students already know. It’s a little bit shocking, but very few schools understand who students already know and how those connections can benefit them. Another step that is particularly relevant for high schools is equitably expanding networks to increase access to opportunities and really taking career exposure, exploration, and experience seriously—ensuring that those career exploration activities are not just about transferring information about the world of work, but actually fostering connections to the world of work. That means providing opportunities to actually meet people working in a variety of fields, to engage in “career conversations” with those people, so that young people aren’t just hearing about jobs in the abstract, but actually being given the opportunity to critically think about their own pathways and their own future possible selves in dialogue with professionals.

Postsecondary institutions also have distinct opportunities. The first is that there’s a deep literature on persistence, and in particular, the power of near peer mentors to drive that persistence. The second thing is the opportunity for postsecondary institutions to pay even more attention to internship access as a real difference-maker in young people’s career prospects post-school. And then lastly, in postsecondary, there is a unique opportunity to shift to a more outcomes-oriented market. Right now, we still basically fund enrollment and don’t measure outcomes as rigorously as one might hope. But if and when that shift occurs, we think that alumni networks are going to matter even more. Internships and access to experiential and work-based learning is something that can be harder for traditional postsecondary institutions to really scale with quality. Their alumni network should be one of the first places they’re turning to scale those opportunities for students, and data suggests that that’s not currently happening at scale.

ESG just released a new framework for the role that advising can play in helping students find success in postsecondary and career pathways. In your view, how are advising and the development of social capital connected? What are some ways that the promotion of social capital could be better integrated into advising practices?

As much as formal advising is part of the structure of high school and postsecondary education, data shows that students actually turn to a variety of people who are not their formal advisors for guidance, advice, and inspiration. Paying attention to who those sources of guidance and advice are, and what channels to a diverse set of perspectives are being brokered on behalf of students feels like a domain where we could see more innovation.

Innovations in advising can also leverage the power of near peers; the idea that someone is a few steps ahead of you, and can then lend real-time, relevant, credible advice is very different from a formal advising structure with a checklist of steps like filling out the FAFSA. Many of those formal structures and checklist approaches have been necessary, but insufficient traditions in the advising space. Investing in more near-peer strategies could move beyond just continuing to double down on the traditional structures that have disproportionately failed low-income students and students of color, to actually diversify the sources of guidance and advice that we surround those young people with to ensure that they have better information, inspiration, and credible guides.

How can leaders leverage the Christensen Institute’s new playbook to build and strengthen their students’ networks?

We published this playbook on the heels of the past few years of research into what a number of innovative organizations that treat social capital as a programmatic outcome are actually doing. How are they designing their models and the student experience to reliably or more reliably foster those webs of support? How are they fostering those expanded networks to expand opportunity? We hope it can serve as a guide for leaders who are starting to embrace this important role that social capital plays in the opportunity equation and say, “Well, we know relationships matter, we want to take this to the next level, strategically. We want to be more data-driven, in terms of how we measure students’ access to networks, and we want to be more deliberate in terms of how we design student experiences to be more sort of relationship centric.” To that end, the playbook lays out five steps that really are the core themes that emerged from our research into holistic, equitable relationship models:

- Take stock of who your students know.

- Shore up support networks.

- Expand networks to expand opportunities.

- Leverage Edtech that connects.

- Build networks that last.

You can learn more about each of these steps here.

How can state, district, and higher education leaders consider leveraging their stimulus funding to invest in helping students develop social capital?

I would just go back to the power of webs of support and expanding networks to expand opportunity. Our young people need webs of support and resilient networks to overcome the next wave challenges they will face after this year of social distancing. Any student support plan needs to have a human component to it—not just amount to a series of interventions. Beyond shoring up support networks, leaders also have a role to play in terms of ensuring students are expanding their networks in an equitable manner. There’s obviously a lot of energy around career pathways, but much less energy about the networks that do or don’t form around those pathways. We need to pay closer attention to the fact that if those pathways are not growing students’ networks more equitably, they are not going to produce a more equitable labor market.